‘I’m supposed to be here’

PhD student José Carlos Díaz shares his remarkable path from Cuba to chemical engineering at U-M.

PhD student José Carlos Díaz shares his remarkable path from Cuba to chemical engineering at U-M.

By Marcin Szczepanski and Nicole Casal Moore

[Newscaster: In Cuba the scope of Hurricane Ian’s wrath is now visible.]

Narrator: In the fall of 2022, Hurricane Ian destroyed parts of Florida and knocked out power across all of Cuba. The hurricane made the headlines, but the power and water shortages happened daily in Cuba.

José Carlos Díaz: The shortages in electricity and power in Cuba have caused an uproar from the people of the island. You need water to produce clean energy but you also need a lot of energy to produce clean water. Four billion people around the world face water scarcity issues; that means that almost half the world faces these problems.

Narrator: José Carlos Díaz hopes to find a solution to this global crisis. He’s a University of Michigan chemical engineering PhD student, and he grew up in Cuba.

José Carlos Díaz: I think the most striking thing as I was growing up was the fact that there was a lot of issues with electricity. Doing the homework was usually with candlelight, because the government would constantly shut down the power to save a little bit more energy. As a small kid, I would usually think about, “Oh, what if we created a battery that would last maybe like, more than twenty-four hours so that during the night we can have some energy, some electricity.” I play around with small batteries and try to understand that I was far away from building anything like that.

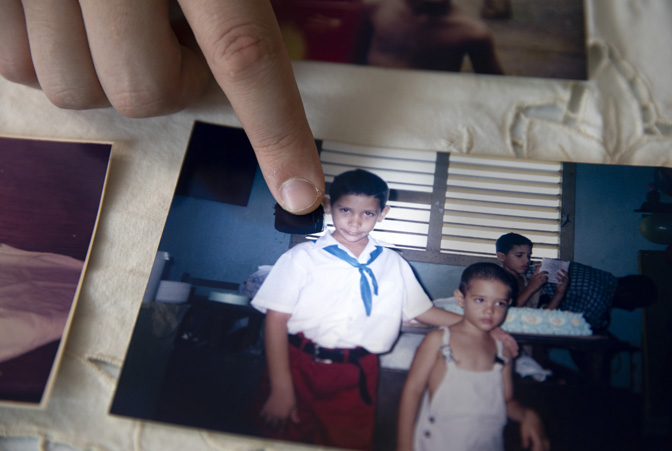

Narrator: In 2011, fifteen-year-old José, his five-year-old brother and their mother escaped from Cuba.

José Carlos Díaz: It was my mom who decided to flee the country. She saw that our future there was not going to go very well.

Rosalina Milthet: I was thinking, “I want better life for my son. I want different life, different life to me.”

José Carlos Díaz: And, in the middle of the night, you know 2 A.M., 1 A.M, I think it was, we got into a car, went to one of this speed boats basically, and we took off. It was almost like a horror movie, like, I didn’t know what was happening.

Narrator: The Smugglers took the family to a port in Mexico, and after a couple weeks there to the U.S. border. At the border, the family asked for a political asylum. Madea’s Family settled in Miami, where José faced new challenges.

José Carlos Díaz: Now all of a sudden, I have to start in high school, late in now a high school that spoke another language that was not the language that I spoke. Very, very tough moment for me, yeah. My first class was biology, and I had a keen love for biology, and there I found some sort of like a safe space because, again, science didn’t really have a language for me, in a way. So it was easier to just look at the books and see what they were trying to explain, so through science and through going through the biology class and trying to use the microscopes again and trying to talk to my teacher, and then chemistry class too. That’s how I started learning English and then becoming a little bit more proficient and less scared to talk to to other people.

Narrator: José went to a community college in Miami, then to John Hopkins for his undergraduate degree, and finally to the University of Michigan for his PhD.

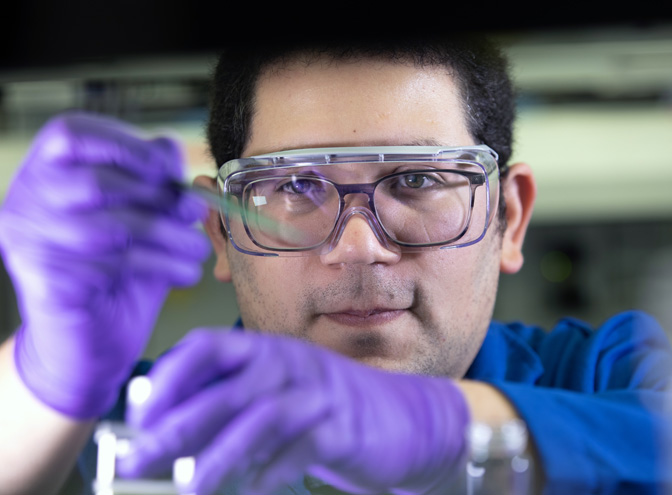

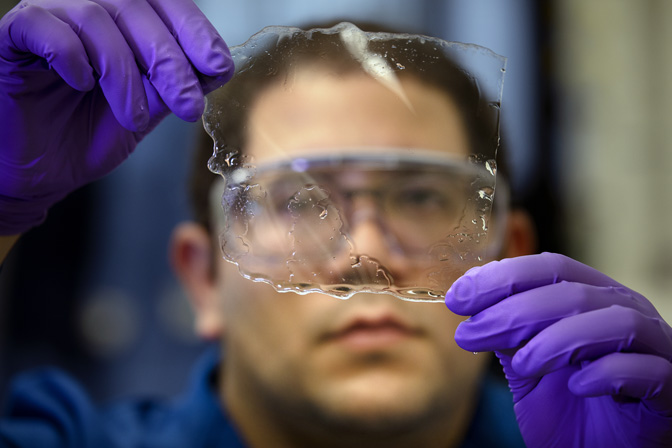

José Carlos Díaz: At the University of Michigan, I worked with Professor Jovan Kamcev from the chemical engineering department. Our research is based in understanding the transport, or how different molecules move in polymer membranes. These membranes are important for applications like batteries for example, other aqueous batteries, they can power great-level houses and cities. But also our lab focuses on desalination. We also focus on these types of filters, these membranes, that can selectively permeate water to one side while the ions are kept on another side, and then you get fresh water. Being able to desalinate water from available resources, like sea water for example, taking sea water then passing it through a filter and getting fresh water. That’s important for you know a lot of people in the world, especially islands like my country, Cuba, where I come from, where there isn’t a lot they can do to get fresh water.

Jovan Kamcev: I think we, so far we’ve done some pretty promising work and we actually do talk with industry quite a bit, so Jose actually has one patent that we submitted, a patent application. We’re in the process of commercializing some of the membranes.

José Carlos Díaz: Coming to the United States, it has been an amazing experience. I realized the countless possibilities that I have now. Basically, my mom’s dream was for her two children to have as many possibilities as possible for them to study whatever they wanted, and to do whatever they wanted in life. My hope is that through my research and my outreach events, I can offer a little bit to this community, to the United States, basically. A little bit of my intellect, as this was you, know, country by choice, as a lot of us immigrants say.

Rosalina Milthet: Leaving Cuba was the best decision in my life.

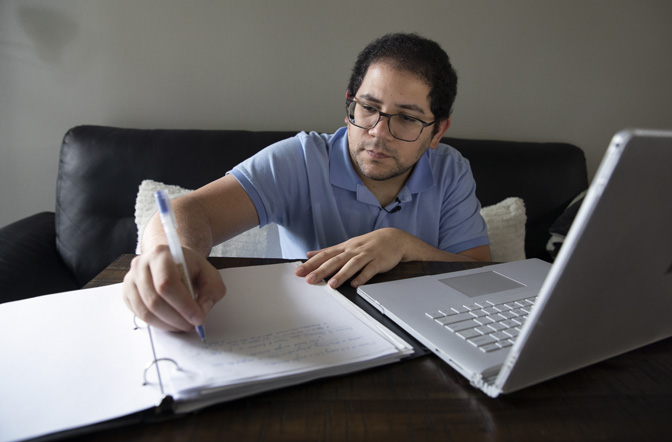

José Carlos Díaz was just 11 years old the first time his knack for engineering and love of science merged and made the world better for the people around him.

The microscopes were broken at his middle school in the southern town of Boniato, Cuba. He remembers the disappointment he felt on the day his teacher told the class they wouldn’t be able to peer inside plant leaves. He had wanted so badly to see live cells.

So the curious sixth-grader took matters into his own hands. He asked the school’s director if he could try to fix the 60-year-old instruments. It took him months, but by the end of the semester he had reverse-engineered seven working microscopes out of parts from the original 23. And every sixth-grade science teacher got one.

“I felt really proud in the sense that I built something that was going to help other students learn what I wanted to learn too about cells and biological systems,” Díaz said.

Today he’s a doctoral student in chemical engineering whose research aims to solve some long-standing problems in his home country–unreliable access to both electricity and fresh water. The membrane technology he’s developing with assistant professor Jovan Kamcev could advance both grid-scale batteries and seawater desalination.

Over 15 years and 1,300 miles–some of it across the Caribbean Sea–Díaz’s journey has taken him from a microscope prodigy in rural Cuba to an ion-diffusion researcher at one of the top chemical engineering programs in the United States.

Díaz was born during the decade-long era of economic crisis in Cuba known as the Special Period, when the fall of the USSR in the early ’90s cut off the nation’s primary trade relationship and source of petroleum for transportation and electricity. Energy and food were rationed. These difficulties cemented the Cuban mantra “Hay que inventar y resolver,” which translates to “You must invent and solve.” The people of the island adapted, turning to bicycles and organic farming. But in many ways, the country has yet to fully recover.

“The government’s attempt to save energy would frequently leave us without electricity in the evenings, forcing me to finish my homework by candlelight,” Díaz recalls. “It was really difficult to even have some sort of normalcy without electricity, though as kids we enjoyed that it was easy to play hide and seek in the streets.

“Countless times, my imagination created scenarios in which I solved the energy problem in my country by inventing a powerful battery that could last for ages.”

Díaz’s mother, Rosalina Milhet, had grown up under Fidel Castro, whose complicated communist regime had brought electricity to rural areas and improved healthcare and education across the nation, even while it suppressed free speech and jailed and tortured dissidents. She had become a well-positioned lawyer for the Ministry of Tourism. But as her children grew, she grew increasingly frustrated that their living conditions continued to falter.

“I wanted a better life–a different life–for my sons and for me,” Milhet said.

She decided they would flee in the fall of 2011. At the time, Cubans who made it to dry U.S. land were allowed to stay and offered a path to citizenship.

Díaz was 15 and his little brother was 5 when Milhet woke them up in the middle of the night to leave for the United States.

“She told me to be very quiet and not to ask any questions,” Díaz said. “We got into a car, went to one of these speedboats and we took off.”

The boat was fast, he recalls. He quickly got used to the rocking motion. His little brother slept. After seven hours, they docked in Mexico. From there, they traveled by land to the border. Milhet presented the paperwork to prove they were Cuban, and the next day, with the help of family and friends who were already in the U.S., they flew to Miami. This would be their new home.

The transition was hard for Díaz. He hadn’t had a chance to say goodbye to his dad’s side of the family. And he had just been accepted to one of the best high schools in Cuba. Yet he found himself in a place where he didn’t even speak the language. The school was bigger than he was used to. In his first days, he got lost a lot.

“I continuously came late to several classes and my teachers would, like, yell at me because I was late and I needed to get a hallway pass,” he said. “But I didn’t even know what they were saying. So I would just point to my schedule and tell them I’m supposed to be here.”

He felt safest in science class, where he could follow along in textbook diagrams, watch experiments unfold in real time and get back behind a microscope. First it helped him forget his struggle to learn English, and then it provided an environment where he could learn at his own pace.

“Science didn’t really have a language for me in a way,” he said. “Through biology class and trying to use the microscopes again and trying to talk to my teacher, that’s how I started learning English and becoming a little bit more proficient and less scared to talk to other people.”

Chemistry captivated him. At lunchtime, he’d visit his teacher to talk about the fascinating molecules in solar cells and batteries and get an early start on the following week’s reactions.

By senior year, he was taking honors and AP classes. He applied to big U.S. universities, even though the process was a bit mysterious to him and his English was still developing. His history teacher, a fellow Cuban immigrant, advised him to pause. He recommended community college, where Díaz could likely get a scholarship, take more time with the transition, and eventually transfer to a larger university.

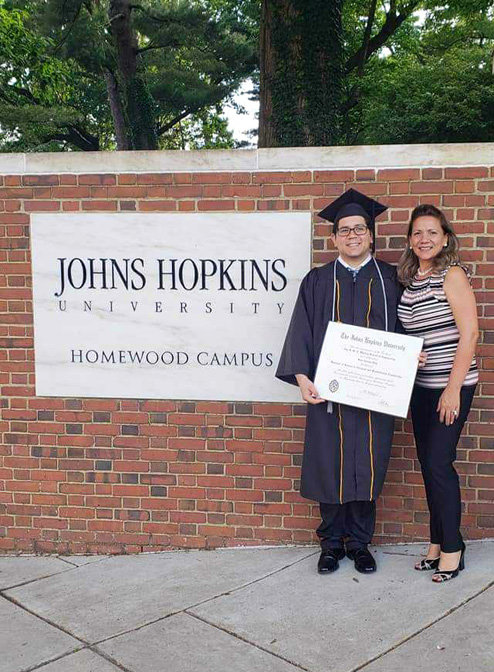

He took the advice and earned an associate’s degree from Miami-Dade College’s honors program. From there, he got into Johns Hopkins University for a bachelor’s in chemical engineering.

Less than five years after leaving his home country, he left his family and moved to Baltimore.

“Arriving to Johns Hopkins was weird and scary,” Díaz said. “It was my first time living alone. I had to do my laundry by myself and a lot of time cook for myself because I didn’t really have too much money to spend on meals at the school.”

He experienced culture shock and a new level of academic rigor that challenged him as never before. He struggled in linear algebra and organic chemistry. On top of that, he was often the only Hispanic student in class. It took him a while to make friends.

Eventually he found his people, and they helped him learn how to study. He also connected with the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers.

“They shared similar stories where their families came to the United States for a better future,” Díaz said. “But also the kind of food that would be at these events was a little closer to home and what I was used to. It was always nice to share food and share our stories together.”

Through SHPE he started volunteering at Baltimore elementary schools and resolved to be a mentor to others like him. Díaz continues this work at U-M.

He also threw himself into research at Johns Hopkins, determined to help find energy solutions for places that need them most. His work as an undergraduate helped to develop a new way to study the performance of lithium-sulfur batteries, promising candidates for long-range electric vehicles and stationary storage of wind and solar energy. He’s a co-author on a 2018 paper in the journal Applied Materials and Interfaces.

“The ability to do research–to have a question and then try to answer it with experiments–I really loved that as an undergraduate,” Díaz said. “I wanted to pursue it more before I went on to industry or anything else. I decided to go to grad school and one of the programs that actually said yes to me was the University of Michigan.”

Michigan Engineering also offered him the financial means to reunite with his mother and brother. All doctoral students receive full funding, including a stipend. The family is together again in Ann Arbor.

Díaz was the first U-M graduate student for his advisor, Jovan Kamcev, an assistant professor in chemical engineering who joined the faculty three years ago. Kamcev was born in Macedonia and moved to New York City with his mother at 10 years old. In Díaz, he found a kindred spirit.

“It takes a special type of student to join an empty lab–somebody who’s not scared of that challenge,” Kamcev said. “He has an inherent motivation to just solve problems, to work hard, to figure things out.”

They built the lab together, figuring out how to assemble equipment and keep it running. The Kamcev Research Lab has since grown to a dozen members. Today they’re developing advanced membranes that are critical components of efficient water purification systems, hydrogen fuel cells and flow batteries that could store enough energy to power a house, or even a city.

Flow batteries are top candidates for storing energy from intermittent sources such as solar and wind. A key step in advancing them to a commercially viable level is developing a more efficient, robust and cost-effective membrane that separates the positively charged anode and the negatively charged cathode. This membrane regulates the flow of ions through the system, ensuring battery safety and performance.

In seawater desalination, membranes offer a paradigm shift from the conventional, energy-intensive method of distilling by boiling. Membranes could separate water from salt ions or any other impurities and provide fresh water in a much more efficient and affordable way.

Four billion people–around half the global population–experience water scarcity at least once a month.

“There’s just not enough fresh water, whether it’s for drinking, for agriculture or for energy applications. This problem is going to keep getting worse as the population grows,” Kamcev said. “Seawater makes up 98% of the water that’s available on the planet, but you can’t directly use it for drinking or for cooling power plants, let’s say, because it contains too many salts or dissolved chemical species. So we need to find ways to purify it.”

Kamcev and Díaz developed new approaches to measure and then control the properties of these membranes and they’ve applied for several patents. Their work provides a sophisticated knob that lets researchers fine-tune a membrane’s capabilities to whatever job it needs to do. Their hope is that it leads to cheaper and more energy-efficient solutions that could benefit developing and developed countries alike, Kamcev says, because water and energy needs are linked in today’s economy.

For Díaz, these are small steps closer to the boyhood dream he had for himself and now holds for his homeland.